80 years ago this week, my “Uncle” Noble and the 9th Infantry Division sealed off the Cherbourg Peninsula eleven days after D-Day during WWII. I was thinking about him while watching the Band of Brothers on TV. When Easy Company jumped into Normandy for their first wartime engagement, Noble and the 9th had already been in combat for over 1 1/2 years.

Noble was Dad’s best friend, after his brothers, Mick and George. Both he and Dad joined the Army when underage in 1940, over a year before WWII started. They were in B Company, 60th Regimental Combat Team (RCT), of the storied 9th Infantry Division.

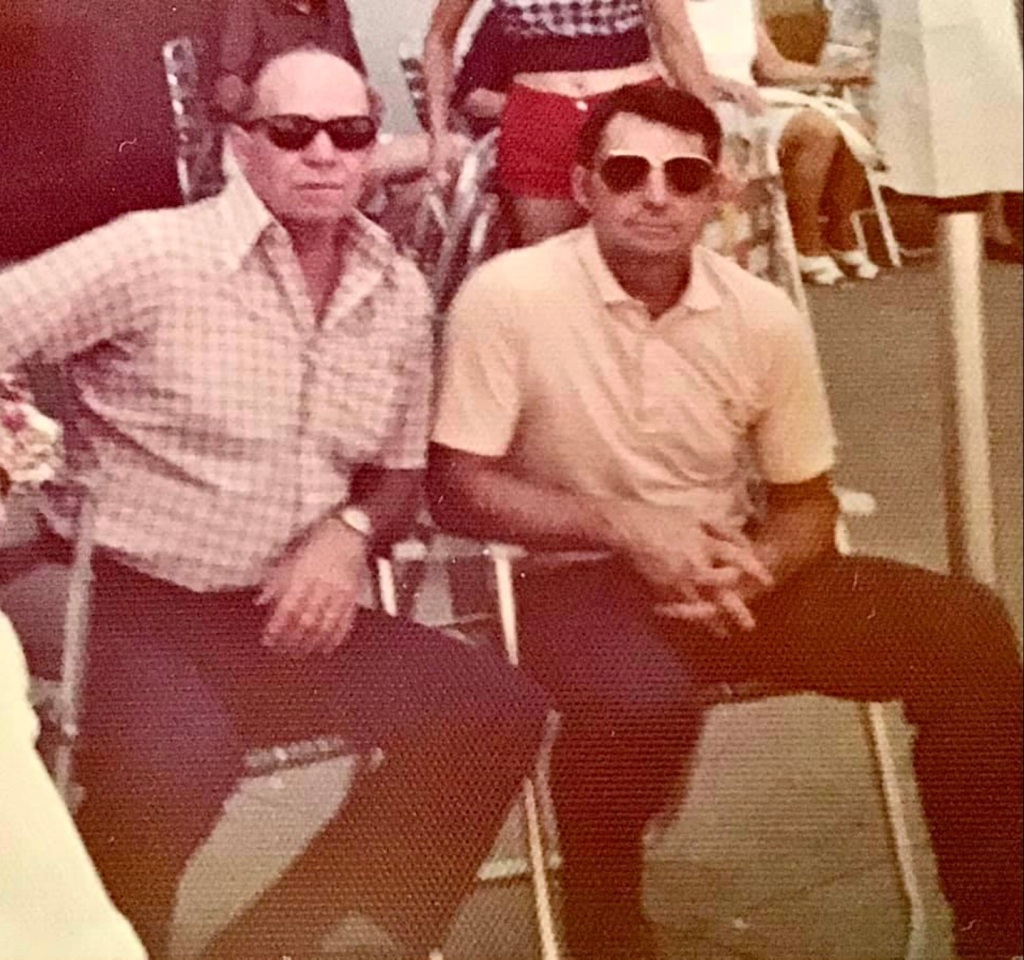

Mom, Dad, “Uncle” Noble and “Aunt” Myra were great friends through the years and got together several times a year. The four of them had a close friendship that lasted a lifetime. I learned a lot about life, and about enjoying life from all of them, but particularly Dad and Noble. They told stories from their time in the Army – almost always funny stories of things that happened. The serious stuff? The stories of death and destruction? Those didn’t make it to the kitchen table where folks gathered, drinking coffee and listening, as these two combat veterans told their tales.

Noble’s actual WWII story is interesting. It’s one you can’t really tell without also telling the story of the 9th.

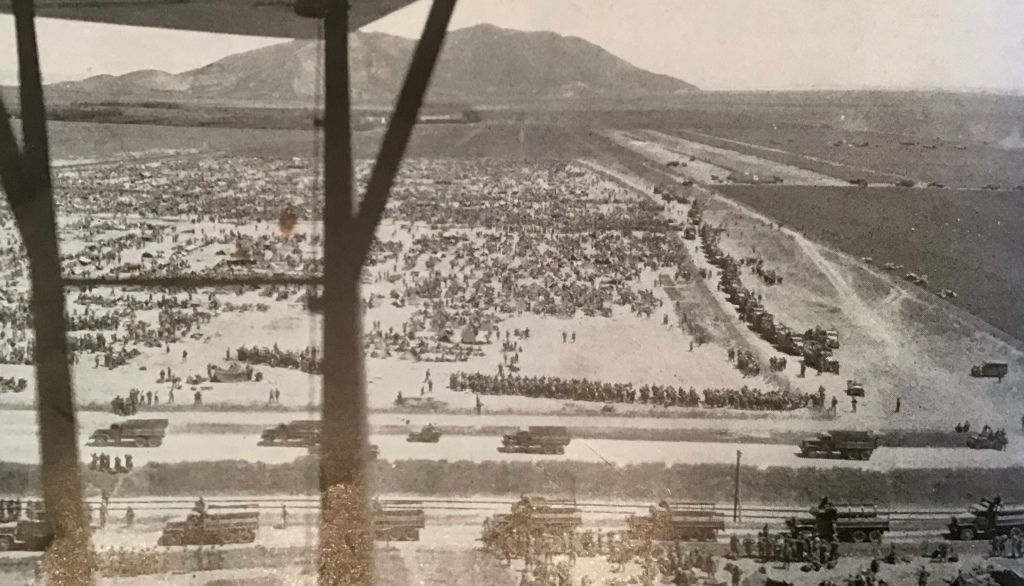

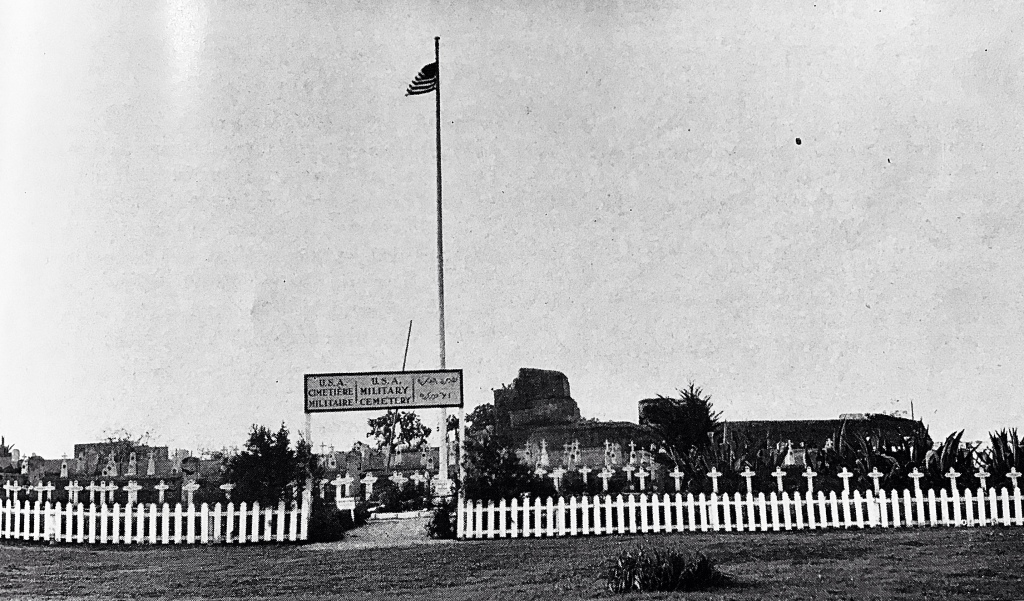

Dad and Noble’s wartime experience started on November 8th, 1942, when the 9th took part in the Invasion of North Africa. Until D-Day happened, it was the largest wartime amphibious assault ever. After three days of battle, they took Port Lyautey, Morocco and the Vichy French surrendered. After some downtime, in January of ‘43, the 60th RCT was the only unit selected to take part in a review for President Roosevelt who was at the Casablanca Conference. Dad and Noble were both there and told us funny stories of the comments in the ranks as Roosevelt passed their unit in a jeep for the review. “Hey Rosie – who’s leading the country while you’re over here?” “Hey Rosie – Who’s keeping Mamie warm while you’re over here?”

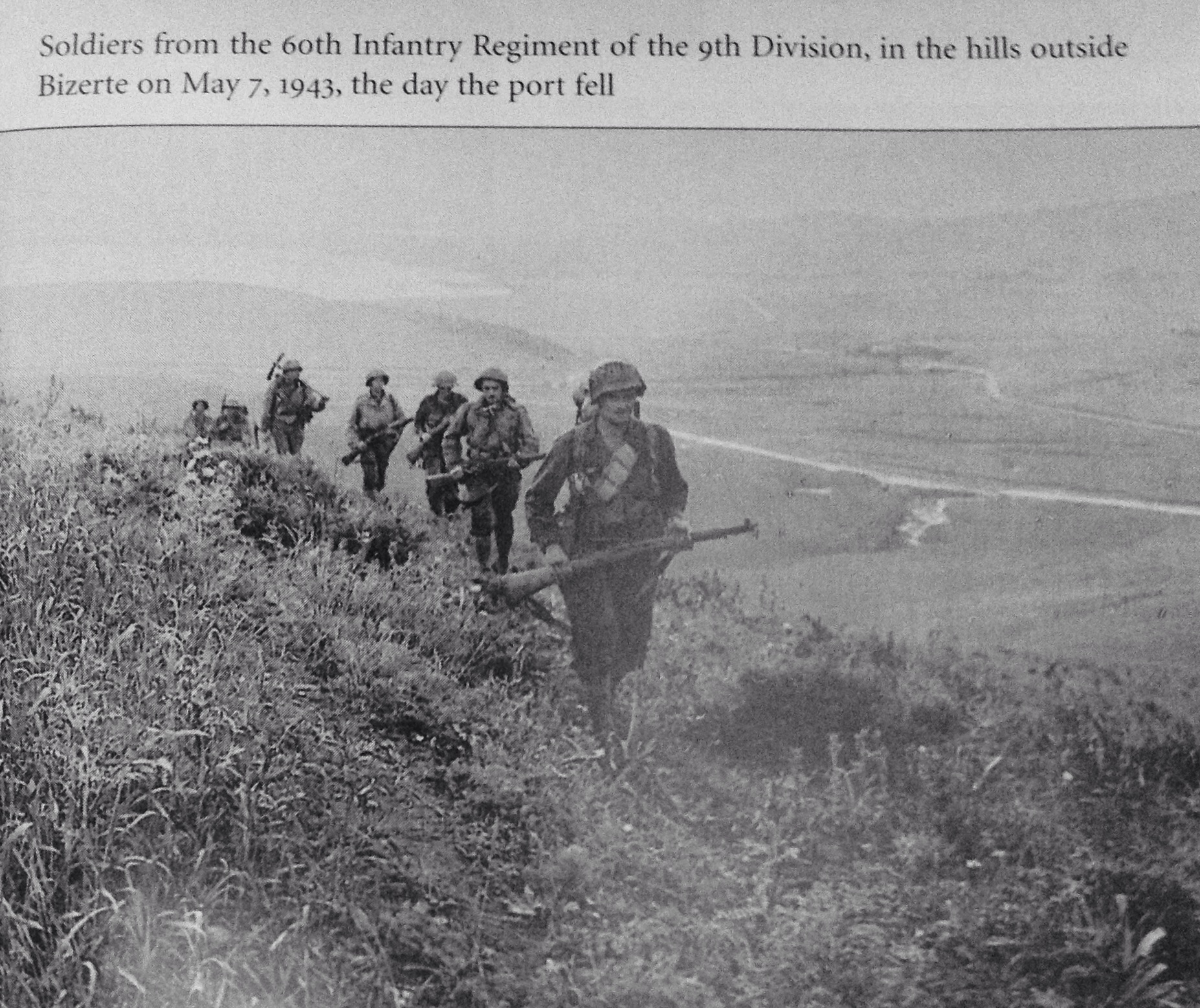

Things got tough again after that. Starting in February, they fought their way across Algeria and then Tunisia. Station de Sened, Maknassy, Bizerte – forgotten names now, but deadly locations in the spring of ‘43. The Germans eventually surrendered at Bizerte, on May 9th, 1943, just over a year before D-Day.

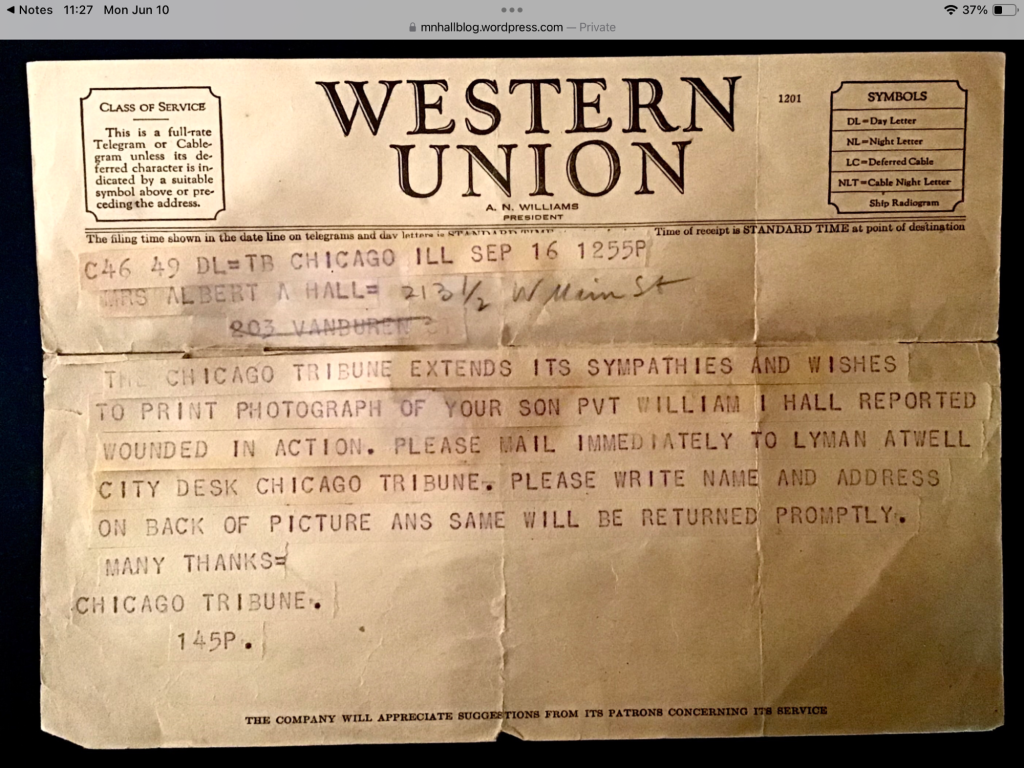

The 9th wasn’t finished though. A little over two months later, in July of ‘43 they took part in the invasion of Sicily. The 60th conducted the famous “Ghost March” through the mountains of Sicily, which the Germans originally thought were impenetrable. Dad was shot three times there, and almost died. It took them a few days to evacuate Dad to an aid station, and then a hospital. The war was over for him and they eventually sent him back to the States.

In fact Dad’s wounds were so severe, Noble thought he had died, or would die shortly. As they evacuated him, Noble and the 60th continued the fight. 38 days after the invasion began, Sicily fell on August 20th. Noble was there when Patton addressed the Division on August 26th, congratulating them for their efforts.

In September of ‘43, the 9th deployed to England for rest and refitting. With just over nine months until D-Day, the 60th had already fought in four countries on two continents.

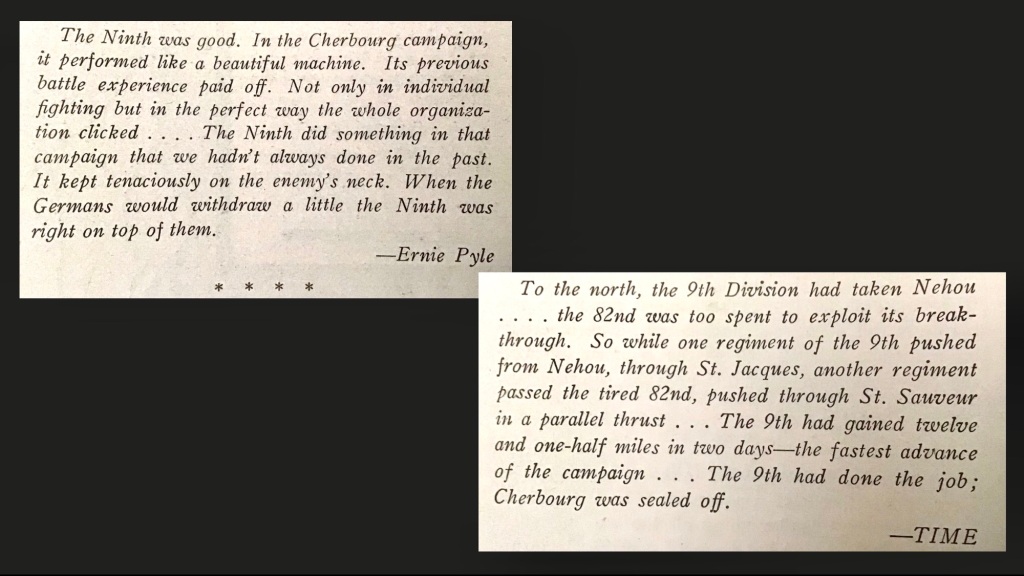

On June 10th, D-Day plus 4, Noble and the 9th landed on Utah Beach. Their mission? Attack towards Cherbourg and cut off the peninsula. This they did and on the 17th of June, reached the ocean on the other side of the peninsula, and eventually, captured the port of Cherbourg itself. If you’ve forgotten your history, Cherbourg was critical for the allies to establish a port on the Atlantic Seaboard. Back home, the news singled out the 9th for their efforts.

From there, they started on the great chase across France. The 9th advanced over 600 miles by the end of September thru France and into Belgium. In 3 1/2 months they were engaged in three major campaigns and were only out of action for a total of five days.

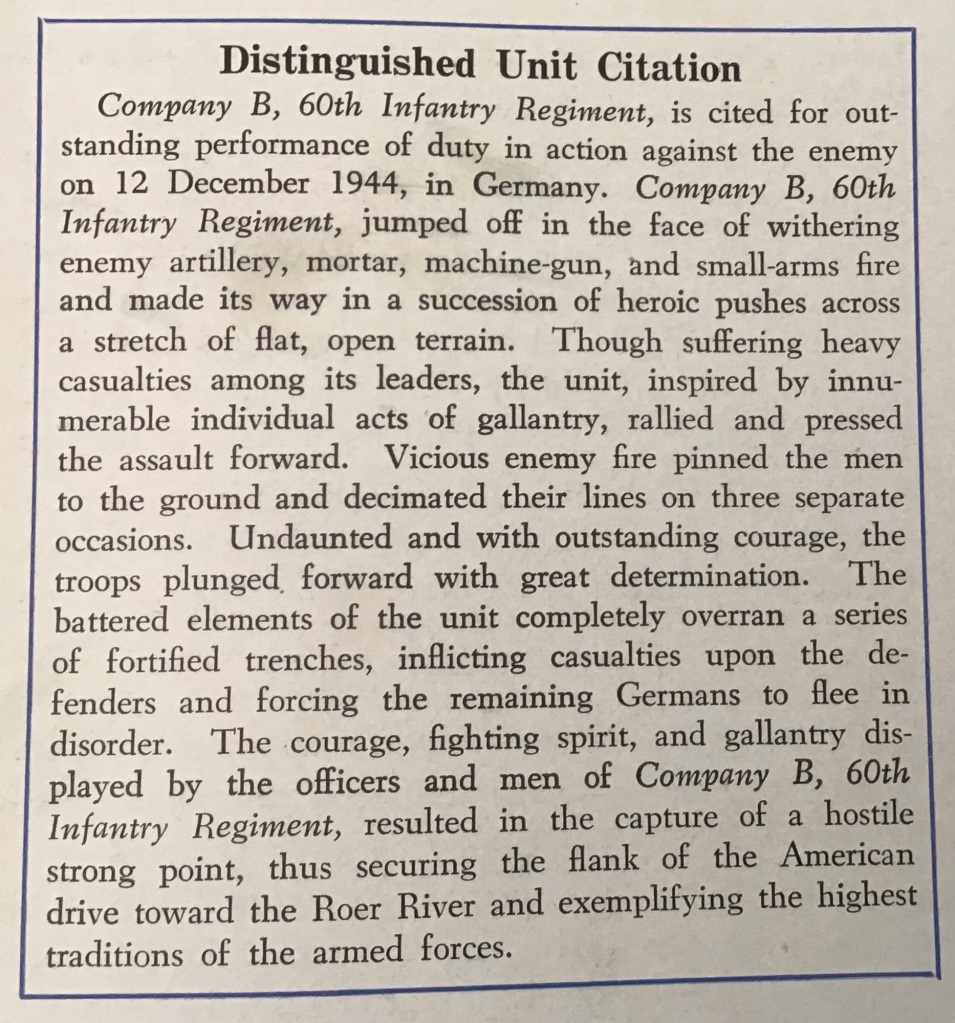

The 9th was among the first units entering Germany itself. For actions on December 12th in the Hurtgen Forest area of Germany, Noble’s unit, B company 60th RCT, received a Distinguished Unit Citation for combat actions in Germany. At the time, the company probably had around 80 or so men.

Just after the 12th, The 9th was pulled out of the line due to the heavy casualties they had sustained. It was “resting” in the Monschau Forest area of Belgium, when on December 16th, 1944, the German winter offensive, the “Battle of the Bulge” started. Thrown back into combat, the Division beat back the enemy at the northern edge of “The Bulge”.

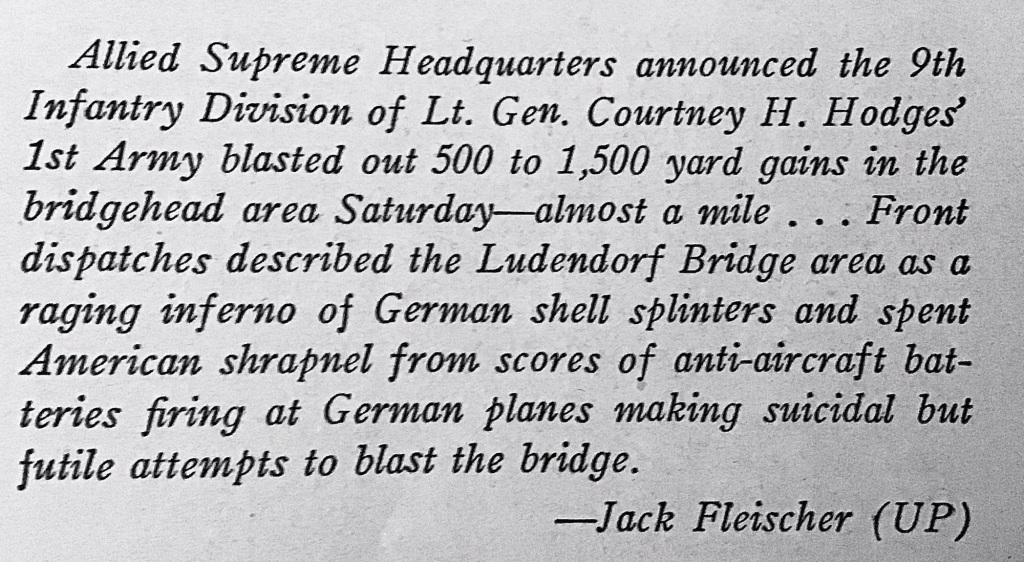

The Battle of the Bulge, The Ardennes, the fight across Germany to the Rhine River – Noble saw all of that. On 7 March, when the American 9th Armored Division captured the bridge across the Rhine River at Remagen, Noble and the 60th RCT were among the first Infantry units to cross under heavy fire and defend the bridgehead from the East side of the Rhine.

On across Germany – The Ruhr, The Hartz Mountains… On April 26th, 1945, a patrol from the 60th RCT linked up with the Russians at the Elbe River. The war in Europe officially ended on May 7th.

Noble spent 2 1/2 years in combat, fought in seven countries and survived without a scratch. Miracles do happen.

In 1950, a minor miracle also happened.

In July of that year, a knock came at my parent’s door and Mom answered. A young couple was standing there and wanted to know if William Hall lived there. Mom said yes and called Dad. All of a sudden there was yelling, and exclamations, and hugging, and dancing and back pounding – it was Noble, and his new wife Myra.

It turned out Noble and Myra were traveling from a vacation in Wisconsin back to Southern Illinois where they lived, when they passed our hometown – Ottawa. Noble thought Dad had died in Sicily, and then remembering he was from Ottawa, decided to stop in and see if he could find Dad’s parents and offer his condolences. He looked the name William Hall up in the phone book, and stopped off at the local VFW to see if anyone knew of Dad or his relations. They then drove to the address from the phone book, assuming it was my grandfather’s home. Instead, he and Dad saw each other for the first time since August of 1943 in Sicily.

I was born in ’55 and named Max Noble Hall in honor of Noble. I always enjoyed seeing him and Myra over the years during their visits. Later, at West Point, and then while spending my own time in the Army, I often asked myself if I was measuring up to these men from B Company of the 60th RCT.

I feel so lucky having known them and having heard the stories Noble and Dad told. It’s only in the last decade I’ve matched those stories up to the details in history books. I can tell you they greatly underplayed what they did for America and the free world. What I wouldn’t give for another day with Noble and Dad – listening to the stories, and this time, asking more questions.

The “Greatest Generation” is mostly gone now. I think it’s important we not let them, or their stories be forgotten.

Here’s to you Uncle Noble. Thanks for everything you did for this country and being an influence in my life. It’s a debt I can never repay.

Addendum:

- Some of this blog was extracted from a blog I did a few years ago about Dad and three of his buddies from the 9th. You can read it here if you want: https://mnhallblog.wordpress.com/2016/06/17/dad-deason-boggs-and-noble/

- I relied on the book, “Eight Stars to Victory, A History of the Veteran Ninth U.S. Infantry Division”, published in 1948, as background for much of the factual information in this blog.

The 60th attacked a series of hills on the nights of the 22d and 23d with mixed success. As dad explained “we always attacked at night, but the Germans were well dug in. And they had mines on many of the approaches. The Germans used mines everywhere. The going was very slow.” They did take several of the hills, particularly on the north side of the pass, but the Germans still controlled the south side. Hill 322 was attacked many times but never taken. The advance bogged down, but the US Forces acted forcefully enough to cause the Germans to deploy reserve units, keeping them from engaging with Montgomery and the British, further to the south. Dad said that from where they were, they could actually see the open land on the other side of the pass, even though the Germans still controlled the south side of the pass. That open ground was what the tanks needed.

The 60th attacked a series of hills on the nights of the 22d and 23d with mixed success. As dad explained “we always attacked at night, but the Germans were well dug in. And they had mines on many of the approaches. The Germans used mines everywhere. The going was very slow.” They did take several of the hills, particularly on the north side of the pass, but the Germans still controlled the south side. Hill 322 was attacked many times but never taken. The advance bogged down, but the US Forces acted forcefully enough to cause the Germans to deploy reserve units, keeping them from engaging with Montgomery and the British, further to the south. Dad said that from where they were, they could actually see the open land on the other side of the pass, even though the Germans still controlled the south side of the pass. That open ground was what the tanks needed.